Breadcrumb

This story forms part of a series of dialogues led by writer Rose Lu with previous recipients of the Asia Pacific Arts Awards, highlighting the artists shaping creative work across the region. You can discover other interviews on our Stories page, or via the links at the end of this article.

From the writer: This exchange between me and the Liminal editors, Leah Jing McIntosh and Cher Tan, took place over a collaborative document. It is one of many slow exchanges that we have had over the years.

Rose Lu (RL): Over the years, Liminal has been a propeller, and a rudder in the changing tides of Asian Australian literature. I got to know Liminal through the Slow Currents writing program, a collaboration between Liminal and Satellites. Something that always stuck with me from one of the first sessions, back in 2022, was an observation that the state of Asian Australian literature was about five years behind where Asian American literature was, and that Asian New Zealand literature was ten years behind Australia. Where do you think Asian Australian literature is now?

Cher Tan (CT): It’s come a long way. I remember when I first moved to the continent in 2012 and only found books like Nam Le’s The Boat or Christos Tsiolkas’ Loaded when I was on a search for literature that wasn’t written by white people. Peril magazine existed then, but there didn’t seem to be much else. There was also the Growing Up Asian in Australia anthology, which I appreciated but didn’t relate to as an adult migrant. I’m thinking that if I were to move to the continent now, I’d be spoilt for choice. So much has changed in the last decade alone: Anam and Cold Enough For Snow for example, as Leah mentions. I remember having a conversation with your friend Brannavan [Gnanalingam], Rose, and talked about loving books (particularly from the ANZ region) about “bad migrants” after reading Huo Yan’s Dry Milk. I ended up sending him a fair few books.

Leah Jing McIntosh (LJM): In a way, it’s strange to think about these literary ecosystems comparatively, as they have formed within completely different contexts—and yet still have a clear impact upon each other. I think that’s why Rosabel Tan, the director at Satellites, and I wanted to create the Slow Currents program; to see how we could learn from each other, and also to see where we could go from there. So I do have to say, I don’t know if we’re behind Asian American literature or outpacing writing coming out of Aotearoa; I think Asian Australian literature is its own thing, and I’m happy that Liminal has been able to support writers within this landscape. That said, I think some of the best Asian Australian writing being published at present is porous, and thinks beyond borders—perhaps doesn’t think of itself as ‘Asian Australian’ but maybe just as diasporic, or nationless, or pushes beyond the limits of that ever-overflowing container. I’m thinking here of André Dao’s Anam or Jessica Au’s Cold Enough for Snow; I’m also thinking here of Cher’s Peripathetic. It’s exciting to see writing that reaches beyond received notions of statehood and fractures or fragments or proposes new ways of seeing.

CT: If you consider the number of Asian diaspora in each area, there are more people in the US than in so-called Australia, and then more in the latter than in Aotearoa. That in itself creates a response to the trends and interests in the dominant population, and as a result reflects what types of creative risks minoritised people are willing or able to take.

RL: Liminal is in its eighth year of operation now, and the number eight is lucky in Chinese culture, as the word for 八 (bā in Mandarin) sounds like the word for 发 (fā in Mandarin), which means to generate wealth. It’s been a lucky year for Liminal! In addition to the Impact award from APAA, Liminal also won a special award at the NSW Literary Awards, for exceptional contribution to the literary life of Australia. How have these awards changed the imaginative possibilities of Liminal’s future?

LJM: As Cher and I mentioned when receiving the Impact award earlier this year, it’s important to remember that fifty, or even twenty years ago, we would not have had the privilege to make Liminal, and it’s doubtful that we would have been recognised for it, if we had.

We are so deeply indebted to the intergenerational efforts of our Asian Australian elders, and the resistances they committed to our shared future. I think these awards remind us how lucky we are to be able to do this work, and they’re also a good reminder that we must do something with this luck.

CT: Yes, it’s important to understand that we are beneficiaries of the Representation-Industrial-Complex (as I call it), a byproduct of the model minority. As such it feels like a great responsibility to not pander to that in our successes while being mindful of the work of our Asian Australian elders too, some of whom were never adequately recognised for their work due to racism. You see Asian names in old literary journals who you no longer hear of, or they’ve gone on to pursue careers elsewhere.

I also think it’s crucial for Liminal to think about Asianness not through Chineseness too, as it’s so easy to do (particularly as Chinese people ourselves). But having that kind of recognition definitely widens the scope of our reach, which hopefully allows for more creative collaborations with other Asian Australians we may not know of.

RL: In Liminal, Leadership, and the Long View, you talk about the importance of time, and how work over multiple generations builds to political change. It’s a beautiful and considered essay, and was written slowly and collaboratively over two years, much like many of Liminal’s initiatives. When and how did time become a guiding factor in Liminal?

LJM: This is such a beautiful question, Rose. Liminal was meant to be a short project, only twenty interviews, and somehow it spilled over into something else—we have over 200 interviews now, have commissioned award-winning art and writing, have published two books, run national literary prizes and more—it’s a bit absurd looking back at it. I don’t know if time is a guiding factor, but maybe it is rather an openness to continuing something we believe in—and knowing that all good things take time.

CT: Yes, very much agree with Leah. A lot of our work hinges on the idea that artmaking and writing are never life-or-death situations, and things can always wait until it is able to reach its fullest potential—a decolonial understanding of time, perhaps. When I first got to know Leah through Liminal, I never saw it as becoming something it does now; it just felt like a fun little project you’d do with friends like when you’re in a band. I don’t think I really understood Liminal’s significance and weight until much later too, but even then that still remains in the background (maybe it only really comes into the foreground when we win a prize, for e.g.). It’s not to say that I don’t take Liminal seriously, but perhaps that it speaks to a particular ethos in the way we work.

LJM: I think Liminal as a fun little project created with friends is actually exactly what it is.

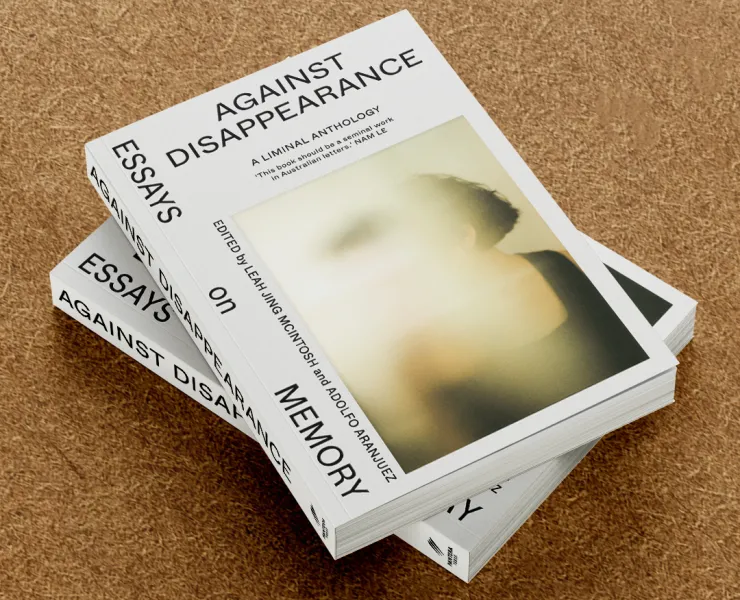

Image: Against Disappearance, edited by Leah Jing McIntosh and Adolfo Aranjuez.

Liminal was the 2025 recipient of the Impact award.

Rose Lu

WriterRose Lu is a writer from Pōneke, Aotearoa, currently based in Naarm. She gained her Masters of Creative Writing at the International Institute of Modern Letters in 2018 and was awarded the Modern Letters Prize for Creative Nonfiction. Her first essay collection All Who Live on Islands was published to critical acclaim in 2019. She has been in residence at the Randall Cottage (2022) and the Michael King Writers Centre (2024) and was a participant in the Slow Current programme run in collaboration by Liminal (AU) and Satellites (NZ) from 2022-2024. Her undergraduate degree was in Mechatronics Engineering and she has worked as a software developer since 2012.

Photo credit Gabriel Francis

More from this series

Installation view of Seleka International Art Society Initiative’s Hifo ki ‘Olunga 2021, GOMA, 2021 / Commissioned for APT10. Purchased 2021 with funds from Tim Fairfax AC through the QAGOMA Foundation / Collection: QAGOMA / © The artists

In Conversation with Asia Pacific Triennial

Rose Lu speaks with Tarun Nagesh from Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) about the past and the future, and how artists can break free of these types of binary constructions.

In Conversation with Bábbarra Women’s Centre

Rose Lu speaks with Jessica Stalenberg from Bábbarra Women’s Centre on why women’s textile work is neither simple nor secondary, and how a collaboration with Tharangini Studios is reshaping how these practices are valued.

In Conversation with PacifiqueX

Rose Lu speaks with PacifiqueX president Marqy on reviving erased histories, uplifting MVPFAFF++ identities, and building joyful, resilient Pacific queer community in Naarm

In Conversation with Taloi Havini

Rose Lu speaks with Taloi Havini about inheritance, exile, and the long arc of Indigenous sovereignty across Oceania.