Breadcrumb

This story forms part of a series of dialogues led by writer Rose Lu with previous recipients of the Asia Pacific Arts Awards, highlighting the artists shaping creative work across the region. You can discover other interviews on our Stories page, or via the links at the end of this article.

From the writer: I spoke with Taloi Havini, an artist based in Brisbane, Australia, and our conversation traversed through a number of islands in the Asia Pacific. In addition to these physical distances, we also covered the psychic distance between places, due to changes in time, the political climate, and our relationships with ourselves.

Your work engages a lot with the physical land, and especially the landscape of Bougainville and how it’s been affected by extractive capitalistic activities like mining. But then, there’s also the beauty of the place. How do you hold these two competing concepts of beauty and the destruction in your work?

I noticed you used the word “landscape”, and I think that is what the west believes when they look out on a piece of land. They go, “wow, what a beautiful landscape.” However for indigenous people, it’s more than just beautiful scenery. The land gives us sustenance. It’s mountains, rivers, soil, reef, airspace, trees: things that are seasonal and growing. The environment is all encompassing.

Using mediums such as moving image or photography, you can really show the beauty, like for example in my installation Habitat. But often what’s lying beneath these beautiful environments is a sought after resource. Indigenous people from Oceania know that people and organisations who don’t have a relationship to the land only see the land for its monetary value. There are definitely tensions in that, and that’s what I like to pull out in my work.

I’m from Aotearoa New Zealand, and back home Māori ownership of land has been hugely affected by colonisation. Bougainville has been colonised by many countries, and I’m wondering how indigenous people have held onto that land?

The thing about Bougainville is that it doesn’t have the same settler colonial history as Aotearoa or Australia. The majority of the land and atolls are still owned by the Bougainville people, though colonists did come in via the ports to create “crown land”, and so we have two towns that are considered “government land”.

In the 70s there was a big clearing of land to create the Panguna mine, which at the time was the biggest open cut mine in the world. That mine was the catalyst to people wanting their own self determination. The corporations hit a nerve by displacing people off their customary land, and taking the benefits while giving very little back to the people. Since then the people have fought for their own independence, and Bougainville’s 2019 independence referendum is still something that needs to be ratified. We’re waiting to see what happens, as that’s now in the hands of the politicians in Papua New Guinea.

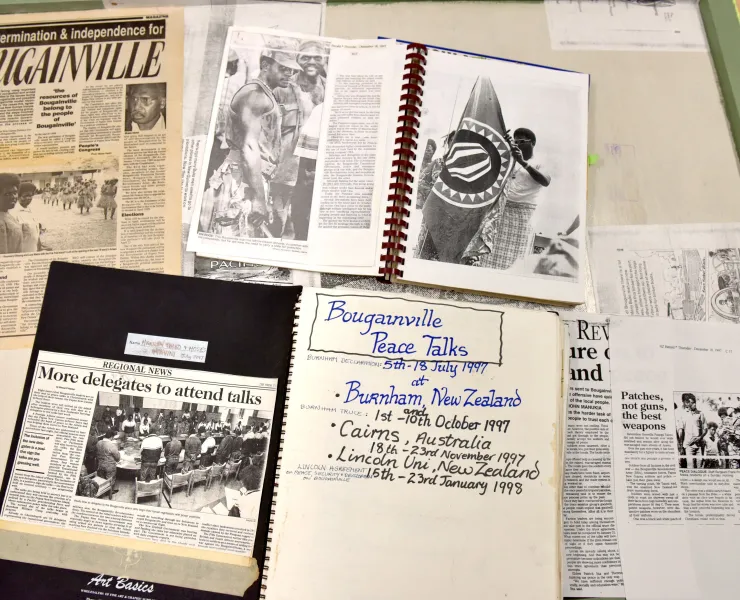

When I was in residency in Otepoti Dunedin, I was going through my parents’ archives, which go back to the 60s. I was looking into these types of issues, and created an exhibition around this material. I got the name Shared Aspirations from a line in a letter that my Bougainvillean father wrote to my mother, an Australian. Australia gave Papua New Guinea their independence in the 70s, and in that process Bougainville became part of Papua New Guinea, even though the people on Martin Island, where I come from, were also seeking independence.

All these tensions come through my work as an Australian artist from Bougainville. I’m born into these issues of indigenous self determination, and all the interrelated social and environmental issues that come with that.

I’m a second generation Chinese immigrant to Aotearoa New Zealand, and something I really admire about your work is your connection to the place that you were born. How have you held onto that connection?

I just go back a lot [laughs]. It’s not easy for migrants, or people who identify as diaspora. I consider myself an Australian artist with Bougainville heritage. I’m also a Bougainville woman. I’ve been brought up in a culture where we take care of our land. I’m a customary land owner, so there’s a portion of land on an island that I’ll inherit, and it's my duty to make decisions and care for it. The land will be passed down through my line, so that’s my connection. Aboriginal people say they go back to country. We don’t say “country” because it's an island, but I say that I go back to my land.

I’ve also held onto the connection through ceremony, culture, and family. We left when I was nine years old because of an armed conflict. At the time, my parents were working for the Papua New Guinean government, but were also speaking out against it. It became politically unsafe for us to stay and so my parents left. We were political exiles. The peace protests in the 90s then enabled my parents to return, so I maintained that connection between Bougainville and Australia.

When I was younger I experienced a lot of racism and I was othered. It’s a strange thing in Australia, where white Australians think that everyone else is not from here. It’s an irony. So I used to go, “yeah I’m not Aussie, I’m from the islands”. But as I’ve gotten older I’ve thought, well no, Australia is full of migrants, and to be Australian is to say you have a voice, and a contribution. I think it’s really important to acknowledge both.

To be Australian is to hold the politicians accountable to this region, to this land, to Aboriginal people, and to all peoples.

In Australia and NZ we use the term “Asian” to connote people who are East Asian—Chinese, Japanese, Korean—but in other places, like the U.K., “Asian” connotes people who are South Asian—Indian, Pakistani, Bengali. Considering your identification as a person who is indigenous, and from the Pacific, when exhibiting in other countries how have they placed you and your work, given the different cultural conceptions that may exist around these terms?

Yeah I’ve exhibited all around the world, and in group shows it’s interesting to see where the curator will place me. I could be placed, say, next to a Malay-Chinese artist, or an Afro-Brazilian artist, or an artist from Saudi Arabia or India. It often makes you curious about how your story

fits in with theirs, and it’s quite incredible to learn about other people’s regions through the artist’s voice. You go, wow, that’s how I want to learn about the world. Not on the internet or via news, but through an artist working in their space. I quite enjoy learning about the world through these curatorial formations of artists. A lot of the time people have never heard of the island where I was born, and that’s great. You’ll never know what you’ll experience when you go into a gallery.

Are there other names for Bougainville?

“Bougainville” is the colonial name for the main island. It was named after the French explorer Louis Antoine de Bougainville, I think he’s like the French version of Captain Cook. Bougainville has over twenty languages, and just like how “Australia” doesn’t have one name, there are many different names for country. “Bougainville” is a colonial way of grouping territories according to colonial imperialism.

The idea of naming one whole island is a colonial idea, not an indigenous one. We have our tribes, we have our people, we have our languages and that’s how we relate to each other. As our people have become enmeshed with the colonial ways and become educated in them, like my father’s generation that went to university, they said well if we are going to live in that world, then we want to live as our own people and self govern, like the Māori and other Aboriginal people. The people have come to own it in their own way.

Has the act of observing and documenting Bougainville changed your relationship with it?

I’d say it’s more about changing the views of the viewer. One of my works, Habitat, showed these scenes of bright blue rocks, which is the result of copper oxidation from the copper coming through the rivers. I’ll be sitting there with someone, and they’ll say, “is that ice?” I find that interesting, that they’ll look at blue water and think it’s ice. Bougainville is a tropical island five degrees south of the equator—there’s no ice. There’s no ice in that part of the Pacific. I’ll tell them no, that’s the minerals, that’s because of the mine. That fascinates me, to be able to change the views of the audience, to change their attitudes and make them aware of the negative impacts of human corporate greed. Show them that that’s what happens when you purely go in for extraction. You can never get that piece of land fertile, or that piece of river fresh again.

So the inverse of that question is to say that it didn’t change my relationship at all. I wanted to change the way people relate to the environment. To show the complexities of something that looked so alluring and beautiful. It could be quite distressing once you realise what you’re looking it.

Yeah I’ve seen an image of the work, and it’s kind of scary how beautiful it is, that particular shade of blue.

Minerals are minerals and the land is the land. It’s not a morally wrong thing in and of itself to be copper in the world. But it’s the use of it at the cost of people’s lives, at the cost of human rights, and land rights. And for only a short period of time. Then the wealth gets extracted and used, and it's over. But the destruction to the environment is long term.

What are the materials or ideas you’re drawn to at the moment?

I’m still working in the archives, it's a long term ongoing project. I took that exhibition from Otepoti Dunedin to Northsite in Cairns. The idea around it is that for us as a family and for my community, how can we work with archives in a materialistic way? I wanted to present archival material in a way that is very present, and with care. It’s done through photographs and newspaper articles, through an installation, rather than through a computer screen.

I’ve also been influenced in my travels, by how other artists and collectives are recording and self authorising their struggles, their stories and their ways. One example is the Feminist Memory Project by the Nepal Picture Library, which I saw at the Istanbul Biennale. Nayan Tara is the artist. She’s a very influential leader in that space.

Another example is Grunt Gallery in Vancouver. They keep the archives of the artists relevant to them. People can talk about how history is recorded and who records history, but in these two small examples, one in North America and one in Nepal, it can show you that archives can exist with artists and with movements, and not just with the state. State archives hold a different story.

Yeah when you let a community collect what they find valuable, they end up collecting different things from what the state might deem as valuable

Yeah that’s right. When I started my Habitat works I bought licenses from the ABC archive and other state archives. I think it’s interesting to look at all kinds of archives and who’s telling what side of the story. It’s much more interesting to get a multidimensional story of people and community experiences.

Image: Working in progress, in studio by Taloi Havini.

Taloi Havini was the 2025 recipient of the Inspire (Individuals/Collectives/Groups) award.

Rose Lu

WriterRose Lu is a writer from Pōneke, Aotearoa, currently based in Naarm. She gained her Masters of Creative Writing at the International Institute of Modern Letters in 2018 and was awarded the Modern Letters Prize for Creative Nonfiction. Her first essay collection All Who Live on Islands was published to critical acclaim in 2019. She has been in residence at the Randall Cottage (2022) and the Michael King Writers Centre (2024) and was a participant in the Slow Current programme run in collaboration by Liminal (AU) and Satellites (NZ) from 2022-2024. Her undergraduate degree was in Mechatronics Engineering and she has worked as a software developer since 2012.

Photo credit Gabriel Francis

More from this series

Installation view of Seleka International Art Society Initiative’s Hifo ki ‘Olunga 2021, GOMA, 2021 / Commissioned for APT10. Purchased 2021 with funds from Tim Fairfax AC through the QAGOMA Foundation / Collection: QAGOMA / © The artists

In Conversation with Asia Pacific Triennial

Rose Lu speaks with Tarun Nagesh from Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) about the past and the future, and how artists can break free of these types of binary constructions.

In Conversation with Bábbarra Women’s Centre

Rose Lu speaks with Jessica Stalenberg from Bábbarra Women’s Centre on why women’s textile work is neither simple nor secondary, and how a collaboration with Tharangini Studios is reshaping how these practices are valued.

In Conversation with Liminal

Rose Lu speaks with Cher Tan and Leah Jing McIntosh on porous identities, resisting narrow definitions, and fostering creativity that transcends national and cultural boundaries.

In Conversation with PacifiqueX

Rose Lu speaks with PacifiqueX president Marqy on reviving erased histories, uplifting MVPFAFF++ identities, and building joyful, resilient Pacific queer community in Naarm